Trampolining S&C Part 2: Head/Shoulder Placement

As many of you may know, I have been a professional

trampolining coach for over 6 years, and I have spent a great deal of time in

those years learning what my performers typically lack and struggle with.

In my first part to this trampolining S&C set of articles was looking at glute/hip drive in somersaults, but this week I’m going to look at something else that comes up exceptionally often, from the humble front landing all the way to ¾ straight fronts and beyond – head and shoulder placement.

There are a few reasons your performers may struggle with correct head placement, and I’m going to go through them shortly, but first of all let’s discuss what exactly correct head and shoulder placement are, and why they’re important.

In my first part to this trampolining S&C set of articles was looking at glute/hip drive in somersaults, but this week I’m going to look at something else that comes up exceptionally often, from the humble front landing all the way to ¾ straight fronts and beyond – head and shoulder placement.

There are a few reasons your performers may struggle with correct head placement, and I’m going to go through them shortly, but first of all let’s discuss what exactly correct head and shoulder placement are, and why they’re important.

Firstly, following on from what was said last time, head

placement will very often effect the line the performer follows in whatever

skill they’re doing. Last time we looked at the head falling backward, causing

excessive lumbar extension, leading to backward travel.

Here’s a quick throwback for you:

Here’s a quick throwback for you:

Source http://course1.winona.edu/pappicelli/Anatkin/assign/JOINT%20ACTIONS_files/Image19.gif

Notice the arch evident in fig. C – that’s not what we’re looking for.

“What we must be wary

of is the propensity of our performers to travel in their back somersaults due

to poor head positioning, often caused by poor posture and muscular activation

during take-off (see above). The head often falls backwards (as seen above,

where the head is no longer in-line with the shoulders) to create rotation, due

to a lack of rotational power produced from the hips.”

So we’re already aware of the damage that can be done by the

head falling backwards, but the same can also be said of the head falling

forward.

For instance, look at this model and look at how the head placement has affected both take-off direction and somersault travel:

For instance, look at this model and look at how the head placement has affected both take-off direction and somersault travel:

Look

at the whole positioning, the body is following directly behind the direction

of the head.

We must be wary of how our performer is using their head in

their skills. I’ve used a front somersault model here but, as I’ve already

stated, this can affect skills from the humble front landing and then virtually

on to infinity if not caught and fixed early.

Now, given the analyses we went through last time, I’d hope you’re sat there thinking “surely he’s not just going to get us telling our performers ‘head up’ and call it a day?”

Well, astute reader, I’m not going to do that. What I am going to do, however, is consider why the head ends up in this position, and if it’s truly the fault of the head itself, or something more subtle…

Now, given the analyses we went through last time, I’d hope you’re sat there thinking “surely he’s not just going to get us telling our performers ‘head up’ and call it a day?”

Well, astute reader, I’m not going to do that. What I am going to do, however, is consider why the head ends up in this position, and if it’s truly the fault of the head itself, or something more subtle…

Anatomy

If you know anything about anatomy you’ll probably kick

yourself for not thinking of this, but when was the last time you looked at

your performers’:

- · Scapulae retraction?

- · Spinal flexion/extension?

- · Acromion-related impingement?

If you’re anything like I was for many years, you probably

never have, not specifically and deliberately anyway. When I started to look

into these issues with my performers, however, the results were startling.

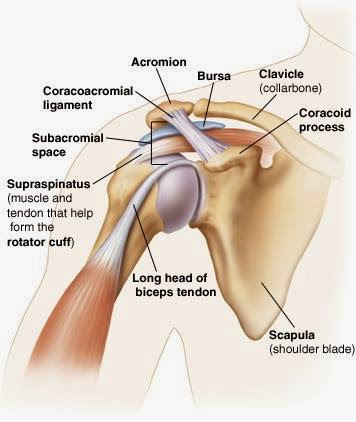

Firstly, let’s look at the acromion (or acromion process), and why that might be the crux of

the issues your performers are facing.

Your acromion process is a bony structure on top of the shoulder blade (scapula), and is a point of attachment for the deltoid and trapezius muscles.

The job of the acromion is to join up with your collarbone (clavicle) to form the AC (acromioclavicular) joint which, as a gliding joint, permits the room in the shoulder ball and socket for the humerus when raising the arm above the head.

Your acromion process is a bony structure on top of the shoulder blade (scapula), and is a point of attachment for the deltoid and trapezius muscles.

The job of the acromion is to join up with your collarbone (clavicle) to form the AC (acromioclavicular) joint which, as a gliding joint, permits the room in the shoulder ball and socket for the humerus when raising the arm above the head.

Source: http://optimumsportsperformance.com/blog/wp-content/uploads/2013/12/shoulder-joint.jpeg

A handy little picture for you to see the different areas we’re talking about.

Now, the ball and socket joint of the shoulder will work

best in its natural position of 30° into the frontal plane (where most people’s

will rest, facing 30° forward), so when the ball (humeral head) tries to move

in the socket it wants to move in the frontal plane; this is because, when in

the scapula plane, the attachment of the supraspinatus is given clearance by

the acromion on top of the shoulder. As soon as you bring that arm out toward

the side of the body, you begin to smash that humeral head and supraspinatus into

the acromion above it; this is known as impingement.

Now I’m not suggesting your performers are putting their arms out to their sides, causing impingement, and therefore not capable of doing a tuck front – what I am saying is that the acromion is key in the performers’ ability to lift their arms directly above their heads. If posture is bad, the acromion will get in the way of the humerus and that’s good night Vienna for a straight arm directly above the head.

So how does the acromion come into play, when you know your performers are lifting their arms above their head in that correct frontal plane?

Let’s go back and look at our postural analysis. Specifically, how a kyphotic posture could be the cause of the issue:

Now I’m not suggesting your performers are putting their arms out to their sides, causing impingement, and therefore not capable of doing a tuck front – what I am saying is that the acromion is key in the performers’ ability to lift their arms directly above their heads. If posture is bad, the acromion will get in the way of the humerus and that’s good night Vienna for a straight arm directly above the head.

So how does the acromion come into play, when you know your performers are lifting their arms above their head in that correct frontal plane?

Let’s go back and look at our postural analysis. Specifically, how a kyphotic posture could be the cause of the issue:

Source: http://www.webefit.com/articles_400-499/ART_433_Img/ART_433_ProperanKyphosis.jpg

Notice the rounded shoulders and tendency to look down – important.

So when our performers have rounded shoulders such as the

young lady above, their acromion process is clearly

not in the correct place for the arm to be directly above the head, because

this would require a much greater ROM to achieve.

Stand up now and hunch over like this lady – imagine you’re at the top of your bounce and trying to look at the trampoline beneath you. Now try to get your arms above your head, pointing at the ceiling.

I’ll wait.

I bet it didn’t happen. If it did, then you’ve either got magical shoulders or you did our little experiment wrong. Go try again.

So we can see from this that the acromion could be the reason your performers are struggling with a straight take off for their forward rotating skills, due to the chance their posture has dictated an impingement scenario, but what can we do?

Stand up now and hunch over like this lady – imagine you’re at the top of your bounce and trying to look at the trampoline beneath you. Now try to get your arms above your head, pointing at the ceiling.

I’ll wait.

I bet it didn’t happen. If it did, then you’ve either got magical shoulders or you did our little experiment wrong. Go try again.

So we can see from this that the acromion could be the reason your performers are struggling with a straight take off for their forward rotating skills, due to the chance their posture has dictated an impingement scenario, but what can we do?

One thing I believe many coaches overlook is the function of

the back, and then the muscles required for that function.

In our example above the lady has rounded shoulders, that’s obvious, but what isn’t so easy to see from the side view is the complete lack of scapulae retraction.

If you, sat in your chair, move your head to look down at your keyboard and let your shoulders round forward, you should feel your shoulder blades slump. That’s the position we were in earlier, so you know you won’t be able to lift your arm all the way up, but do it anyway. Now, keeping your arm in the air, lift your head up to look directly forward. Feel that arm move toward the correct placement a tiny bit? Good. Now draw your shoulder blades back (retract your scapulae) – you should feel a massive change in the position of your arm, and you should now be pointing at the ceiling. That’s where we want our performers’ arms to be on take-off. Just take a note of how much of a difference the scapulae and the direction of the head make in that situation.

Now, let’s take a quick look at the muscles of the back, and focus in on which muscles are going to be predominantly responsible for this scapulae retraction.

In our example above the lady has rounded shoulders, that’s obvious, but what isn’t so easy to see from the side view is the complete lack of scapulae retraction.

If you, sat in your chair, move your head to look down at your keyboard and let your shoulders round forward, you should feel your shoulder blades slump. That’s the position we were in earlier, so you know you won’t be able to lift your arm all the way up, but do it anyway. Now, keeping your arm in the air, lift your head up to look directly forward. Feel that arm move toward the correct placement a tiny bit? Good. Now draw your shoulder blades back (retract your scapulae) – you should feel a massive change in the position of your arm, and you should now be pointing at the ceiling. That’s where we want our performers’ arms to be on take-off. Just take a note of how much of a difference the scapulae and the direction of the head make in that situation.

Now, let’s take a quick look at the muscles of the back, and focus in on which muscles are going to be predominantly responsible for this scapulae retraction.

Source: https://www.acefitness.org/images/webcontent/blogs/blog-examprep-091313-2.jpg

I took the picture with the least annotations to save confusion. You’re welcome.

Hands up (which we can do anatomically correctly now) if you

said rhomboids and trapezius, specifically middle trapezius – you’re correct.

As soon as those scapulae are retracted you no longer need to worry about the acromion process inhibiting your performers’ arms from achieving the correct elevation, because you’ve lined everything up correctly.

I’m aware that there are a lot of people who do gymnastics or trampolining (or just sport/fitness in general) who have no idea where the rhomboids even are, let alone what they do, and chances are your performers will be no different. If that’s the case, yelling “retract your scapula, squeeze those rhomboids!” will be worse than useless. So we’ll come to that later, after we’ve discussed a couple of S&C options that should hopefully enable your performers to properly activate the appropriate muscles and get that posture required.

Before we get into the S&C, however, I just want to touch upon one last thing.

As soon as those scapulae are retracted you no longer need to worry about the acromion process inhibiting your performers’ arms from achieving the correct elevation, because you’ve lined everything up correctly.

I’m aware that there are a lot of people who do gymnastics or trampolining (or just sport/fitness in general) who have no idea where the rhomboids even are, let alone what they do, and chances are your performers will be no different. If that’s the case, yelling “retract your scapula, squeeze those rhomboids!” will be worse than useless. So we’ll come to that later, after we’ve discussed a couple of S&C options that should hopefully enable your performers to properly activate the appropriate muscles and get that posture required.

Before we get into the S&C, however, I just want to touch upon one last thing.

Remember in the list I wrote of things to note earlier I

also listed spinal flexion/extension? Well, I haven’t forgotten about it, it’s

just not a massively pressing issue in comparison to shoulder placement etc.

People are very often prone to being vastly more competent at producing spinal flexion than they are extension, which will often impact their posture (rounded shoulders, slouched forward) and there are a few reasons for this.

Firstly, there’s a social paradigm that seems to promulgate having ‘abs’ as the be-all and end-all of health and fitness, and to be without a six-pack or flat stomach implies a lack of fitness and therefore unattractiveness. Secondly, this social construct of having a flat stomach (etc, etc) is only worsened by the amount of awful advice out there in the fitness world, specifically about training the abs (notice I’m saying ‘abs’ and not ‘core’ – that’s important) which seem to solely revolve around the idea that constantly doing crunches of various kinds will magically remove the fat hiding your abs and leave you with chiselled abs or a flat stomach. This isn’t the case, trust me. Thirdly, if you’re anything like me you coach predominantly teenage girls (aged 12-18). Just consider for a moment how much pressure teenage girls feel these days to be attractive and in-shape, and then pair that with the social construct of abs being king and the lack of good advice on training for a flat stomach, and hey-presto – you have a group of performers who are constantly doing crunches, overworking the exercises that promote spinal flexion at the expense of spinal extension, and are creating over-developed abs, which causes them to slouch, etc.

This is a genuine phenomenon, noted by Collier (2007) and even the Harvard Health Blog (Phillips, 2012).

I won’t go on any further with this, it’s just something that needed noting. Remember: always reinforce a healthy body image to your performers, always reinforce healthy and appropriate training techniques for the core, and keep an eye on the posture of your performers as a result of over-trained spinal flexion.

People are very often prone to being vastly more competent at producing spinal flexion than they are extension, which will often impact their posture (rounded shoulders, slouched forward) and there are a few reasons for this.

Firstly, there’s a social paradigm that seems to promulgate having ‘abs’ as the be-all and end-all of health and fitness, and to be without a six-pack or flat stomach implies a lack of fitness and therefore unattractiveness. Secondly, this social construct of having a flat stomach (etc, etc) is only worsened by the amount of awful advice out there in the fitness world, specifically about training the abs (notice I’m saying ‘abs’ and not ‘core’ – that’s important) which seem to solely revolve around the idea that constantly doing crunches of various kinds will magically remove the fat hiding your abs and leave you with chiselled abs or a flat stomach. This isn’t the case, trust me. Thirdly, if you’re anything like me you coach predominantly teenage girls (aged 12-18). Just consider for a moment how much pressure teenage girls feel these days to be attractive and in-shape, and then pair that with the social construct of abs being king and the lack of good advice on training for a flat stomach, and hey-presto – you have a group of performers who are constantly doing crunches, overworking the exercises that promote spinal flexion at the expense of spinal extension, and are creating over-developed abs, which causes them to slouch, etc.

This is a genuine phenomenon, noted by Collier (2007) and even the Harvard Health Blog (Phillips, 2012).

I won’t go on any further with this, it’s just something that needed noting. Remember: always reinforce a healthy body image to your performers, always reinforce healthy and appropriate training techniques for the core, and keep an eye on the posture of your performers as a result of over-trained spinal flexion.

Now you have all of this information, you need to begin

considering whether your performer’s poor head placement is causing these

anatomical issues, or whether these issues are causing poor head placement.

Moving on – let’s look at some exercises to develop your

performers’ ability to get their shoulder blades retracted, set their shoulders

straight, and keep their head up.

Let’s begin with just simply fixing the posture of the

performer.

If you’re not particularly well-versed with the ins and outs of postural analysis and correction then spotting a postural issue might not be easy for you. To spot rounded shoulders, there’s a simple test you can do – ask them to stand with their hands by their sides, and note which way their thumbs turn. Thumbs pointing medially (toward the midline of the body) means rounded shoulders, anterior point (straight ahead) means no shoulder rounding. I myself would have been prone to thumbs pointing in a few years ago, because I used to train chest and anterior delts like they were going out of fashion, and then my back like it already was out of fashion (vis a vis, never). It’s only been since I changed my training to a more-function/less-aesthetic modality that I’ve seen this issue resolved.

Here’s a video from one of my favourite trainers, Jeff Cavaliere, on how to do the shoulder test, and how to use a resistance band to emulate good posture:

If you’re not particularly well-versed with the ins and outs of postural analysis and correction then spotting a postural issue might not be easy for you. To spot rounded shoulders, there’s a simple test you can do – ask them to stand with their hands by their sides, and note which way their thumbs turn. Thumbs pointing medially (toward the midline of the body) means rounded shoulders, anterior point (straight ahead) means no shoulder rounding. I myself would have been prone to thumbs pointing in a few years ago, because I used to train chest and anterior delts like they were going out of fashion, and then my back like it already was out of fashion (vis a vis, never). It’s only been since I changed my training to a more-function/less-aesthetic modality that I’ve seen this issue resolved.

Here’s a video from one of my favourite trainers, Jeff Cavaliere, on how to do the shoulder test, and how to use a resistance band to emulate good posture:

Next, you can either choose to teach the performer how to

retract the scapulae before teaching them how it feels to have correct

alignment when their arms are up, or vice-versa – that’s your call as a coach.

I personally choose to teach the performer how to retract their scapulae first,

so that’s what we’ll look at now.

Think about the muscles we identified as key in protraction of the scapula, the rhomboids and trapezius, and consider what sort of movement activates these muscles best. You’re welcome to use a multitude of exercises, but here are three of my favourites:

Overhead Press

Via Omar Isuf:

Think about the muscles we identified as key in protraction of the scapula, the rhomboids and trapezius, and consider what sort of movement activates these muscles best. You’re welcome to use a multitude of exercises, but here are three of my favourites:

Overhead Press

Via Omar Isuf:

Bent-Over Row

More Jeff Cavaliere:

More Jeff Cavaliere:

Pull-Ups

Yet more Jeff Cavaliere:

Note: This video is slightly different, focusing on how to get correct form rather than just a demo of the movement. I chose this because of how clearly it shows the involvement of the different muscles of the back.

Yet more Jeff Cavaliere:

Note: This video is slightly different, focusing on how to get correct form rather than just a demo of the movement. I chose this because of how clearly it shows the involvement of the different muscles of the back.

I won’t take much time to discuss these exercises for a few reasons, but mostly because a) the videos each do a fantastic job of discussing the exercises and form etc; and b) I’ve made the assumption this far that if you are interested in this aspect of coaching then you most likely have a passing knowledge of anatomy, exercise prescription and programme design (if this is not the case please contact me before you try to implement any of this) so I see no reason to differ here.

Following on from the exercises to encourage rhomboid strength and engagement, there comes the task of ensuring your performers are able to engage the musculature appropriately, and identify when their arms are in the correct place above their head.

One of my favourite ways to encourage this development is to work on their handstands, because there are certain drills that can be done to encourage a completely straight line of the body (packed core, braced glutes, shoulders in line with head, arms in line with shoulders, etc.).

Here’s a video of Camille Leblanc-Bazinet taking you through the development of the handstand, with some great progressions that I find immensely useful once appropriate strength has been developed:

Again, to reiterate, I’m not going to prescribe a training programme based around these movements in this blog series, maybe I’ll do that in an ebook and release it, who knows (e-mail me or tweet me if you want to see that); this series is just to help you start evaluating some mechanical potential problems, and offering some insight into solutions for the coach.

External Cues

Just like I did in the first part of the series, I’m going

to really quickly just go through

some ideas for effective coaching in this regard, again settling the usage of

external cues.

As discussed last time, the external cue needs to be from without, rather than within, so we need to think of something other than “head up” or “shoulders back” to call to our performers.

As an example, I like to use the environment as a focal point for my performers, such as making them “pick a brick”, where they select a brick in the wall on their eye line that does not require them to look down whilst bouncing, and this can focus them on keeping their head position straight.

I also like to give the external cue of getting the performer to imagine they have a pencil between their shoulder blades they cannot let go of, and that is the impetus for them to keep their shoulder blades retracted and rhomboids squeezed. I just find “squeeze the pencil” works loads better than “shoulder back”, and the evidence would suggest that it is more likely to work for you too (see last week’s discussion on external cues).

As discussed last time, the external cue needs to be from without, rather than within, so we need to think of something other than “head up” or “shoulders back” to call to our performers.

As an example, I like to use the environment as a focal point for my performers, such as making them “pick a brick”, where they select a brick in the wall on their eye line that does not require them to look down whilst bouncing, and this can focus them on keeping their head position straight.

I also like to give the external cue of getting the performer to imagine they have a pencil between their shoulder blades they cannot let go of, and that is the impetus for them to keep their shoulder blades retracted and rhomboids squeezed. I just find “squeeze the pencil” works loads better than “shoulder back”, and the evidence would suggest that it is more likely to work for you too (see last week’s discussion on external cues).

So, I’ve gone on too long again, I think. I’ll wrap it up

there!

I hope you enjoyed the second part of my trampolining strength & conditioning observations and recommendations.

I have planned to do a couple other common faults, but if there is anything you feel I should look at that perhaps you or your performers struggle with, then let me know!

As always, you can get me on Twitter, Instagram, e-mail, and here at Guts & Glory Athletics.

See you soon…

I hope you enjoyed the second part of my trampolining strength & conditioning observations and recommendations.

I have planned to do a couple other common faults, but if there is anything you feel I should look at that perhaps you or your performers struggle with, then let me know!

As always, you can get me on Twitter, Instagram, e-mail, and here at Guts & Glory Athletics.

See you soon…

No comments:

Post a Comment